Times Red Box: Expect a Clear Victory but a Messy Aftermath

May 20th at 12:00am

By Jimmy Leach

The Longfellow of Longsight, Noel Gallagher once pithily summed up the traditional tribalism of politics: “Politics is like football for me. Labour is my team and even if you don’t like a striker, you don’t give up supporting the whole team . . .”

And anyone who has had a sweaty-faced Mancunian in their face in a backstreet pub asking: “Are you a red or a blue”, can attest, that attitude has run deep in British voting patterns. Once you have a team, you don’t change — floating voters would be viewed with narrow-eyed suspicion in the same way as those who say, “I don’t support a team, I just support good football”.

Yet as the class divisions among us become more complex, so do our inherited loyalties. The “brand” of political parties are becoming much weaker and voting habits are breaking. We’ve already seen the methadone of Ukip breaking the addiction to Labour of many in working-class areas and a new battleground is being created where the rules are no longer clear but where we are looking at the strikers, not the team.

Theresa May’s gamble (assuming there’s any risk about it in this testimonial atmosphere election) is that she is a stronger pull than her party. The campaign communications strategy is around her — as the grown-up in the room to be trusted to run the country and the Brexit negotiations. It is “Theresa May’s team”, not the Conservative Party.

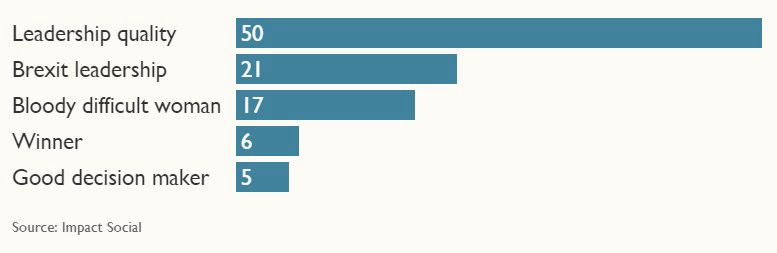

Theresa May: the positives

This week’s manifesto launch, centred on small-state government as a guiding hand (guess who is at the tiller). At the launch in Halifax, May was introduced to the stage by the warm, cuddly figure of David Davis. You don’t do that if you want to suggest you’re one among equals, a Cabinet of all the talents. Nor was May shy about bringing it back to herself: “Come with me as I lead Britain.”

For Labour, it’s very much a personality cult even if the approach to policy is very different. Jeremy Corbyn has had policies coming out for weeks now, and he has set out a vision of the role of the government as a much more dominant figure, with mass nationalisation on the (probably rather distant) horizon. It’s an ambitious vision, with little in common with May’s, aside from the fact that neither seem to have been especially well costed and that the reception for both is centred around not just the policies themselves, but whether the leader is the one to deliver.

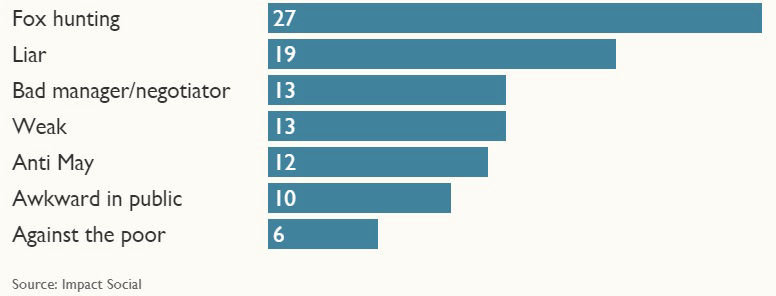

Theresa May: the negatives

To judge which of the centre forwards we trust to fulfil the now leaden analogy, the social media analysis company, Impact Social, looked at online conversations from April 19 to May 18 on the major platforms and comments on open news channels — with the obvious media and political influencers removed and the re-tweets taken out. These are the freely offered opinions of voters (rather than responses to polling questions) and they show things rather closer than you might think.

On the share of voice, Theresa May leads with 1.1 million mentions compared with 900,000 for Corbyn. She’s the incumbent so you’d expect a lead, but Corbyn is being heard.

Of all the mentions where opinions were directly expressed, there were three times as many negatives as positives about May. Much of the data pre-dates the manifesto launch so that is to be expected, but it’s also a function of the Tories’ May-centric communications strategy.

On the positive side, their messages are getting through to the point that they are being repeated right back at them — that she is a “bloody difficult woman” (the phrase May has appropriated from Ken Clarke), that she has leadership qualities, is the one to go out and bat for Britain in Brexit negotiations, and that she’s a winner.

The negative opinions are also about her, not the party, including that she’s a bad negotiator who dislikes the poor, is socially awkward and a liar who’s main enthusiasm is for foxhunting. What comes across most is her apparent coldness and lack of empathy. As Bob Monkhouse used to say, if she could fake sincerity, she’d have it made.

It all shows that the Tory control-freakery around the campaign and May’s robotic repetition of slogans is landing, but not always well. It suggests that her popularity in the polls reflects the view that she might be able to do a specific, Brexit-related, job but few actually like her.

It’s not a problem for this election perhaps, but should she fail to deliver, then there’s trouble ahead. An issue exacerbated because she hasn’t said what she hopes to achieve. Meaningless Brexit phrases simply means we impose our own interpretation on what she should deliver . . . and won’t be happy if she doesn’t.

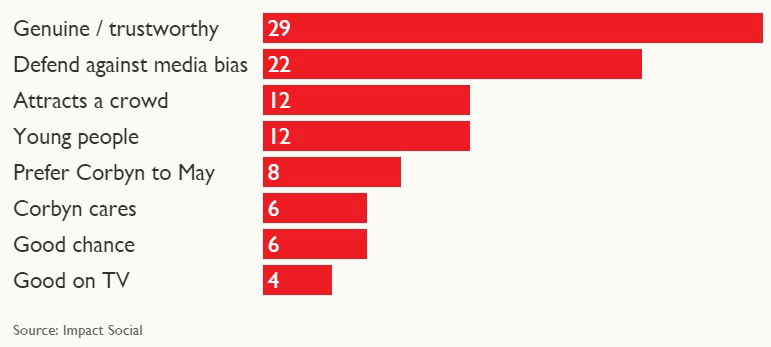

Jeremy Corbyn: the positives

For Corbyn, things are looking a little better than expected. Of the posts Impact Social measured that centred around him, he had a ratio of 61 per cent likes to 39 per cent against. Rather healthier looking at first glance and, again, centred on personality not policy.

In the negative corner, he is derided as a deluded, irrelevant old socialist who is unfit to lead, can’t be trusted and is destroying his party. His actual policies get 22 per cent of the negative conversation, but nothing stands out in the public mind.

A significant number of positive comments for Corbyn centre on supposed media bias against him and the curious phenomenon of the young and enthusiastic crowds who emerge for his public appearances and must feature in the nightmares of Team May as signifiers of a hidden, secret army. Those are the same (sort of) people who view Corbyn as trustworthy, caring and good on TV, with a good chance of winning the whole shooting match.

Which, when you balance this data with the polls, looks unlikely. But, even in the light of May’s poll lead, this indicates that her presumed victory is driven by the weakness of those set against her (the old “if we can’t beat this mob, we shouldn’t be in politics” argument reversed), but also that her popularity is hollow. There’s a Brexit storm brewing and she has failed to define what success might look like in that battle. If she falls short of the strength she’s been claiming, she’s in trouble.

And for Corbyn the picture is mixed too. The polls may be exaggerating his expected defeat and he may do better in the share of the vote than Ed Miliband and Gordon Brown in the last two elections. This would provide him with the case to stay as leader, and hugely prolong Labour’s identity crisis. The social data hints at a support for Corbyn that the pollsters are not finding, and those voices may be at the young end of the demographic — more likely to be on social media and less likely to vote. If they can be stirred, there’s life in this election yet. And even more in its aftermath.

Jimmy Leach is a former head of digital communications in Downing Street